At a meeting in Accra, Ghana at the end of August, senior stakeholders of a major malaria sequencing project met to consolidate lessons learned and plan for significant expansion of malaria sequencing capabilities in West Africa.

“The meeting was a huge success” says Shavanthi Rajatileka, the Sanger Institute’s In-country Operations Lead. “It was a fantastic opportunity to look at the project end-to-end. We celebrated the accomplishments of the first phase, discussed possible challenges we might face in the next phase, and started to build strategies to get around them.”

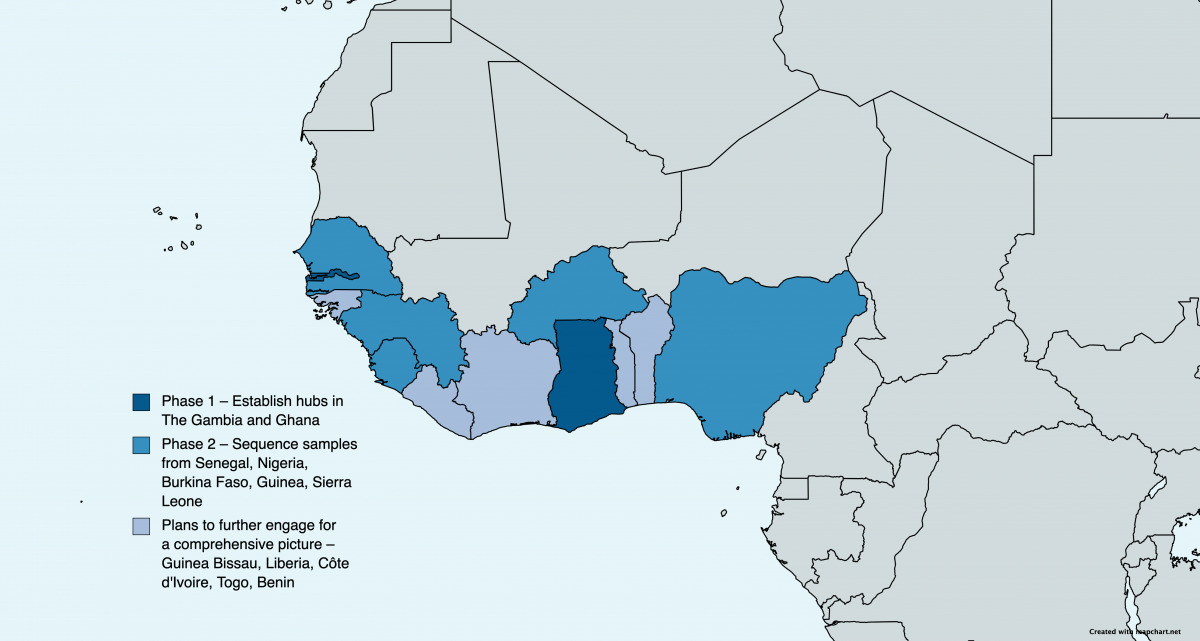

In the first phase of the “Genomic Surveillance of Malaria (GSM) in West Africa” project, funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), amplicon sequencing capabilities were established in Ghana and The Gambia. The COVID-19 pandemic caused delays, but now state-of-the-art equipment, data pipelines, and specially trained personnel are in place, ready to start sequencing samples. The Ghanaian and Gambian labs will act as regional hubs, able to produce the kinds of data that had previously only been possible by sending samples to Sanger.

The second phase, which was formally kicked off at the Accra meeting, will see parasite and mosquito samples collected from around West Africa and sent to the sequencing hubs in Ghana and The Gambia. There are formal agreements with Senegal, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Guinea and Sierra Leone, and there were discussions to build further partnerships, filling in the map of West Africa.

“GSM West Africa is the first of a new kind of genomic surveillance project,” says Alfred Ngwa, Associate Professor at the MRC Unit The Gambia and co-Principal Investigator of the project. “We are prioritising relationships with health policymakers and implementation workers in order to translate data into action. We need to start articulating planned science and interventions with the affected populations and health workers, not just in our laboratories.”

With these labs operational, drug- and insecticide-resistance profiles can be shared in near real-time with National Malaria Control Programs, who can use them to inform malaria interventions.

“Mosquitoes and malaria germs don’t recognise national borders,” says Lucas Amenga-Etego, a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Ghana and co-Principal Investigator of the project. “This emerging West African genomic surveillance network will be key to getting a fuller picture of malaria spread and evolution. By better understanding the biology, we can more effectively target interventions.”

During the three-day meeting, stakeholders from NMCPs and research institutes in West Africa, as well as partners from the UK, discussed learnings from the first phase. Discussions included fundamental science as well as logistics, communications, public engagement, and compliance.