Are parasites building a resistance to antimalarial drugs? Which mosquitoes are spreading malaria in a specific village, and have they become more resilient to insecticides? Will new vaccines continue to save lives?

These are all research questions which can be explored using genomic data. And these explorations can be more effective if that data is collected, sequenced, and analysed in the countries where malaria is present.

Malaria researchers in Africa and beyond want to see this “in-country” genomic analysis become a reality. Steps are being taken across the continent to make that happen.

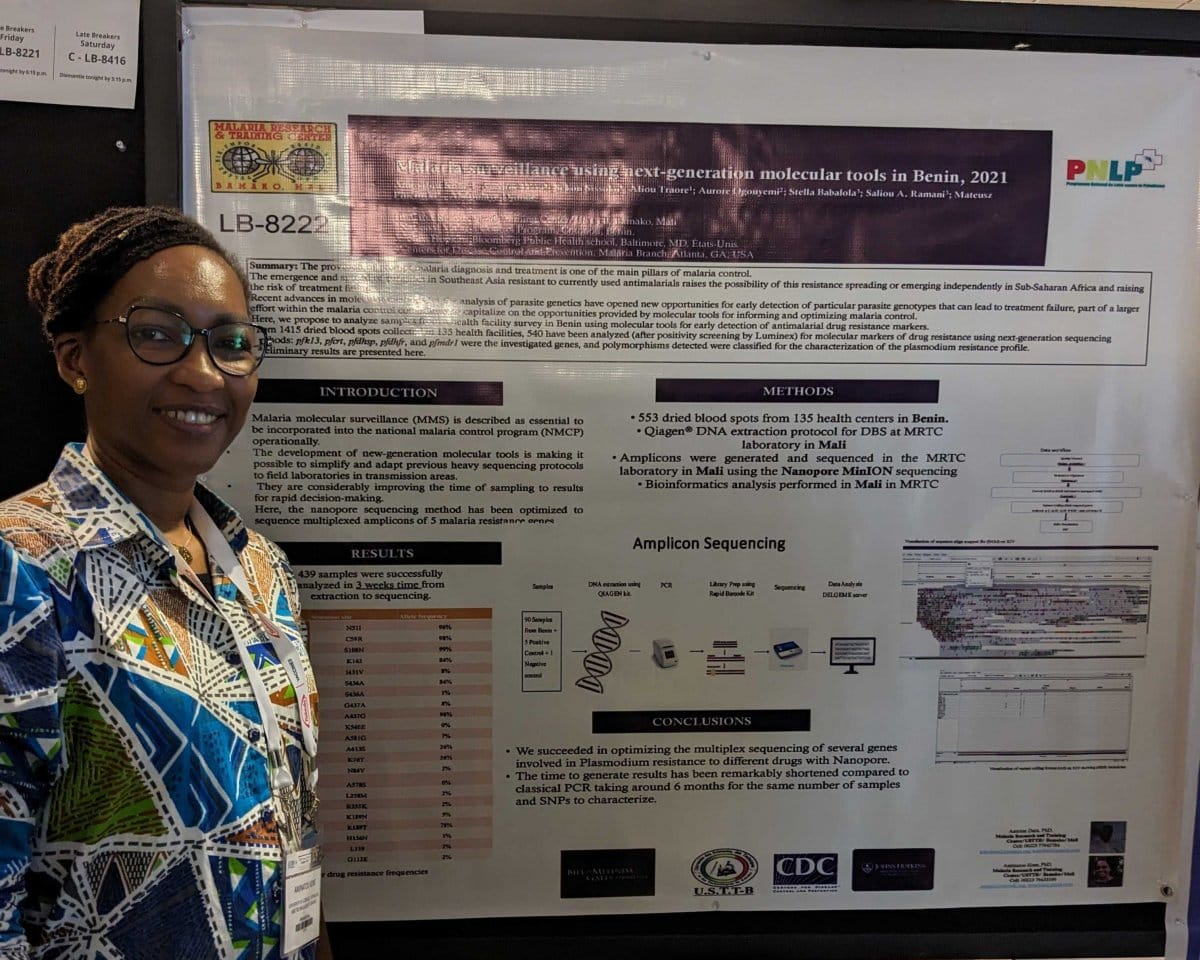

A molecular surveillance laboratory in Mali

Dr Aminatou Kone has seen plenty of changes in her 21 years researching malaria at the University of Sciences, Techniques, and Technologies of Bamako (USTTB) in Mali. Changes to fieldwork, to molecular techniques, the addition of more surveillance sites, and the growth of a bigger, more multidisciplinary team. Aminatou’s lab is currently focused on the most seismic change yet: achieving genuine independence in genomic operations – to be able to collect, sequence, analyse and use data without samples ever having to leave Mali. The benefits of this are clear.

“The time for processing is much quicker. You get your answer fast,” says Aminatou, who describes how data that previously took six months to generate may now take only three or four weeks. “This is really important when you work where the disease is happening. To be able to get your answer, to do what you need to do to contain epidemics, to contain transmission seasons, to contain whatever is happening at that time.”

“The time for processing is much quicker. You get your answer fast,” says Aminatou, who describes how data that previously took six months to generate may now take only three or four weeks. “This is really important when you work where the disease is happening. To be able to get your answer, to do what you need to do to contain epidemics, to contain transmission seasons, to contain whatever is happening at that time.”

Developments in Mali are part of an international effort across Africa and Southeast Asia to build integrated malaria molecular surveillance laboratories in the countries most impacted by the disease. The establishment of these new laboratories, five of which are already operational, is being supported by the Genomic Surveillance Unit at the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

In the past, samples have been collected in malaria-endemic countries, then shipped to facilities abroad, such as the Sanger Institute in the UK, to be sequenced and analysed. The logistics and compliance take time, not to mention the need to have partners willing and able to work on the samples in the first place.

Another benefit of having an independent genomics pipeline running in Mali is the flexibility it offers Aminatou and her team.

“It gives you the room to do many more analyses. Genomics is a large domain when it comes to research questions about a given disease. When you send [your samples] abroad, partners will send back an answer to your given question. But if you can play with your own data, you can pull so much more information, orientate it towards what you really want to see. This independence is critical for African researchers to overcome questions in the field [of infectious disease research].”

Technology and training

Technology and training

The application of genetics to Mali’s fight against malaria has a decades-long heritage, thanks in large part to the work of Professor Abdoulaye Djimde. He was integral to the establishment of the MalariaGEN initiative and now leads the dynamic and growing team to which Aminatou belongs.

Investment in people is key, and Aminatou has watched the team expand. “There are lots of people involved now: epidemiologists, statisticians, molecular biologists, physicians with different specialities. It’s become a more and more multidisciplinary team.”

Establishing ongoing training is important for keeping pace with scientific developments, for both long-standing team members and a new generation entering the field via internships and further studies. “For them, genomics is quite new, it’s interesting and exciting,” Aminatou observes.

Access to the latest genomic technology is also crucial. The team currently has four sequencing machines: one Genetic Analyser SeqStudio, one Illumina sequencing machine (MiSeq), and two MinION machines from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) in the central laboratory of Malaria Research and Training Center-Parasitology (MRTC-P) in Bamako. Two further ONT machines (a GridION and MinION) are available in the labs run as part of the Pathogen Genomics Diversity Africa (PDNA) project. The team is looking into procuring a fourth MinION.

Aminatou sees different and complementary benefits from the ONT and Illumina technologies. “In the African context, you have to think about the speed, the cost effectiveness, the efficiency. Nanopore has the advantage in the field – you can take it in your pocket. The protocol is easy to use and it’s really fast, so if you have a quick question you can use the Nanopore technology.”

Aminatou sees different and complementary benefits from the ONT and Illumina technologies. “In the African context, you have to think about the speed, the cost effectiveness, the efficiency. Nanopore has the advantage in the field – you can take it in your pocket. The protocol is easy to use and it’s really fast, so if you have a quick question you can use the Nanopore technology.”

“You can’t take an Illumina machine [into the field]. But it has the advantage in well-established central labs. We want to establish a really strong sequencing lab, to be a technical support, and to adapt the protocols for new questions. Illumina technology is really important there.”

“Both of them have an advantage for us. So we are investing in both – as long as the procurement [for example, of consumables such as reagents used in the chemical reactions] is allowing us to use them.”

‘Not an easy task’

Mali’s genomic surveillance laboratory is around 70 percent towards full implementation, assesses Aminatou. An important obstacle now is to establish a reliable supply chain for the routine procurement of reagents and consumables required for implementing genomic surveillance.

“Doing research in Africa is not an easy task,” acknowledges Aminatou, who describes procurement as a real bottleneck. But she sees hope, however, as many genomics-focused labs across Africa are moving in the same direction.

“I think collaboration is one of the main ways of overcoming these challenges. If we are in a group I think [procurement] will become easier. So suppliers know we in Africa constitute an interesting market. We have a lot of support already, but it will never be too much support from external collaborators, for training and helping in procurement. At least until we are fully independent.”

Despite the challenges yet to overcome, Aminatou is excited by the vision for the future. “We don’t just want to be a genomics lab, we also want to support disease surveillance for the whole country. We want to be able to put in place training and support for the next generation of young scientists. Because we know that genomics is one of the key sciences for the future of handling infectious diseases.”

Technology and training

Technology and training