Using open-access data available through the Malaria Vector Genome Observatory, Sophia and colleagues have recently identified a cryptic taxon within the Anopheles gambiae complex, which has tentatively been named the ‘Pwani molecular form’. This discovery emerged from a collaborative research effort and is detailed in a new pre-print that sheds light on the taxon’s unique characteristics.

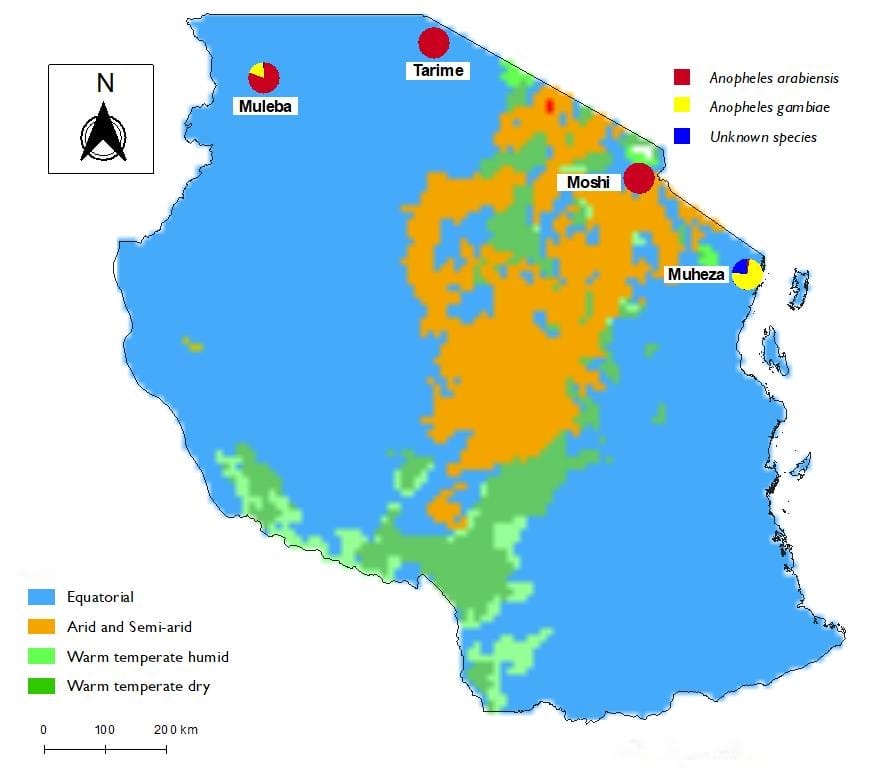

Found along the coasts of Kenya and Tanzania, this mosquito exhibits fascinating traits that set it apart from other species in the complex.

Sophia explains, “Most An. gambiae complex species are freshwater mosquitoes. But the Pwani molecular form seems to be more prominent on the coast, like Anopheles merus and Anopheles melas. This is significant because it suggests this taxon could play a role in malaria transmission during the dry season when freshwater mosquitoes decline.”

Her research also uncovered another critical detail: the Pwani molecular form lacks insecticide resistance. While this might seem like good news, it raises questions about its behaviour and adaptability. “If this mosquito is predominantly biting outdoors, like Anopheles arabiensis, it may evade traditional indoor control measures such as insecticidal bed nets and sprays. That makes understanding its ecology and behaviour even more urgent,” she adds.

Sophia explained that she and the research team had delved deeply into genomic data analysis to uncover and validate the identity of the cryptic taxon. Initially, the team identified samples of Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis collected in Tanzania, noting that the genetic data also pointed to the identification of a distinct group that didn’t align with either species – or with Anopheles coluzzii, which historically had not been identified in East Africa. However, when a study published earlier this year reported Anopheles coluzzii in Kenya, it prompted her to expand the analysis.

“The first thing I thought about was: what if it’s Anopheles coluzzii? So we introduced coluzzii into our analysis to see whether it groups with it,” she explained. Recognising the taxon’s coastal restriction, they also incorporated data from Kenya and Uganda, and that’s when they identified a similar group on the Kenyan coast. Despite initial hypotheses, they used these results to rule out Anopheles coluzzii, Anopheles merus, and other known species within the complex, such as Anopheles quadriannulatus, which is also a saltwater species found on the coast of East and Southern Africa.

Sophia emphasises that the implications of this discovery may be far-reaching. “Another cryptic taxon was recently discovered in the coastal regions of West Africa. We really do not know how these cryptic taxons affect the efforts towards malaria control,” she explains. The ongoing analysis of whole genome data of Anopheles mosquitoes, which enabled this breakthrough, is driving the identification of these elusive taxa, including the Pwani molecular form.

“It’s quite interesting because most of the recent discoveries of cryptic species in the Anopheles gambiae complex have been from West Africa, there hasn’t been any recent discovery of cryptic taxa in East Africa,” says Sophia. She believes that more research will enhance our understanding of malaria vector dynamics, and also highlights the urgency of incorporating such discoveries into both regional and global malaria control strategies. “Our current control methods are very generic and not tailored to target species-specific characteristics of the mosquitoes that have adapted to survive in [different regions],” she notes.

Finding inspiration through collaboration

Sophia has always been driven by a passion for problem-solving, and her work in malaria research is no exception. “My career background is actually from a quantitative side rather than the biology side,” she explains. Grasping the biology of malaria vectors, in addition to the computational techniques required for her work, involved a steep learning curve. “The most fundamental thing about using data is understanding what it’s telling you. Without subject knowledge, interpretation becomes difficult.”

Fortunately, she found mentors who guided her through the complexities of malaria vector biology and genomic data analysis. As one of the participants of the inaugural MalariaGEN-PAMCA training course in data analysis for the genomic surveillance of African malaria vectors, Sophie credits the learning and support she received during the course with helping her tackle the challenges of her research.

Sophia says that she found confidence and inspiration through the vector training course. The course, which has brought together African malaria researchers and public health professionals since 2022, provided a platform to learn alongside people from diverse backgrounds. “[People came with] expertise in molecular biology, entomology, and data analysis, and I got to interact with and learn from the group,” she says.

The collaborative environment fostered by the training course wasn’t just about learning — it was also about teaching. Sophia’s experience as a tutor during the programme’s second cohort became an important moment in her journey. “You learn more by teaching others,” she reflects. “Sometimes you realise you don’t understand a concept as well as you thought, and you have to dig deeper. But as you succeed in explaining it to others, you feel your understanding getting better and better.”

The bigger picture

Sophia’s work goes beyond genomics. As part of her PhD, she is exploring innovative ways to track key biological threats to malaria control identified by the World Health Organisation, including insecticide resistance, drug resistance, rapid diagnostic test failure, and invasive species like Anopheles stephensi.

“The fact that we are now discovering cryptic taxa adds to the list of threats. In one way or the other, we really do not know how these cryptic taxa affect the efforts towards malaria control, and more studies need to be done to understand and to incorporate them in the malaria control strategies,” she explains.

In addition to leveraging tools like genomics, artificial intelligence, and open-source data, she plans to incorporate social sciences into her research. “I will be looking at the stakeholders’ (including researchers, funders, public health) understanding, perspectives and opinions on the key threats. How much an area of research is represented and funded will affect how many outputs there are on a particular threat, so this is useful information to support malaria control.”

As Sophia reflects on the opportunities that have shaped her journey so far, she acknowledges the importance of bridging gaps in the malaria space. “It’s about having a holistic approach to malaria control. I’m glad that this also gets to be a part of my PhD.”

Last year, Sophia was part of a panel of early-career malaria professionals at the MalariaGEN-Target Malaria X Space conversation. Read a summary of the discussion.

Explore recent pre-prints and publications on cryptic taxa, insecticide resistance, and more on vector genomic surveillance using data available through the Malaria Vector Genome Observatory